The rapid growth in wireless phone subscribership in Africa has been hailed as the “missing link” (Kelly, Minges & Gray, 2002) to improved telecommunications access on the continent. Despite the proliferation of mobile phone users in Africa, however, a significant proportion of the population does not own a mobile phone. Unlike most developed societies where telecommunications is acquired and used on an individual basis, in developing countries systems of shared access such as telecenters and cybercafes are being experimented with as alternative methods of expanding access to telecommunications.

With the possibilities offered by wireless telephony, a variety of formal and non-formal sharing arrangements are emerging at the level of end-users. Some of these arrangements reflect truly innovative responses to available technology, the existing telecommunications environment, and the needs of individuals and organizations. All of them lead to broader access to telephony for end-users.

The Ghanaian case

In recent months a large number of roadside and mobile wireless telephone service providers have emerged in some Ghanaian towns and cities. These are run by individuals who purchase a wireless phone handset (which may be in the form a cell phone, or may look like the traditional landline handset), and use it to retail airtime to the general public. Because the operators use prepaid units to power their phones, there is no direct relationship between them and the mobile phone companies. Most of these operators seem to have started within the last 6 months of 2004.

The system currently operates mainly on the Spacefon network hence most of the services are advertised as “Space-to-Space” services (Figure 1). The handsets are fitted with a Spacefon chip, thus providing callers with direct access to Spacefon subscribers. While there is talk about other cell phone companies offering similar equipment, this development was a direct response to interconnection problems between Ghana Telecom (the incumbent telecommunications service provider) and Spacefon, which had become the premier mobile phone company in the country.

|

| Figure 1: Space-to-Space wireless phone operator with client in Osu, Accra |

It is not yet clear exactly how this system began, but one account (personal interview of a former Spacefon employee) has it that in order to overcome the obstacles Ghana Telecom was putting in the way of callers trying to reach the Spacefon network, Spacefon distributed to telecenters specially designed telephone sets fitted with a Spacefon chip to enable consumers at the telecenters bypass Ghana Telecom when they wanted to make calls to Spacefon subscribers. Somehow, these phones found their way into the hands of some entrepreneurial individuals who began to offer this service outside of the telecenter system. Spacefon was reportedly not averse to this development, especially since it all functions on a prepaid basis.

According to one operator, although the phone sets are designed in such a way that only Spacefon chips (and therefore only Spacefon prepaid cards) can be used with them, the phones are not manufactured by Spacefon and so technically, one could replace the chip with that of any other cell phone company. In fact these operators do not buy the phones directly from Spacefon, but from shops that sell telephone equipment, although some Spacefon agents may carry the phones as well. It is therefore possible to use them to provide access to in-network calls for callers on all networks. A number of other mobile phone companies (including Ghana Telecom) are reportedly exploring this option and it is unclear what is holding them back. Some operators are already advertising mobile-to-mobile services in anticipation of such opportunities (Figure 2). Whether or not these developments will drive Ghana Telecom to modify its anti-competitive stance and make access to and from its networks easier for rival mobile phone subscribers remains to be seen. Indications are that it is leaning more towards facilitating some comparable service of its own, rather than opening up its networks.

|

| Figure 2: Space-to-Space operator advertising (as yet unavailable) mobile-to-mobile service |

In terms of cost, being the dominant network, calls to Spacefon subscribers from these roadside service providers cost less than calls to other networks. For example, Space-to-Space calls cost between 1500 and 2000 cedis, while Space-to-other-networks calls cost about 2500 cedis per unit (Figure 3). Depending on which network is being accessed one unit may provide one to four minutes of talk-time.

|

| Figure 3: Sample of prices for wireless phone calls from Space-to-Space operators |

According to some operators interviewed in Osu and Tema in the Greater Accra region of Ghana, this system is proving a fairly lucrative source of income for them. However, they were unable (and in some cases, reluctant) to provide more detailed data such as cash flow, profit margins and time taken to recoup initial investment. Based on a few responses, the initial outlay for this business is approximately 7 million cedis, which is the cost of the telephone set including 1000 free units. Once the free units are depleted, operators top up with 3000-unit prepaid cards purchased from Spacefon, which cost 900,000 cedis. There is also obviously some expense incurred for a table and or shed, some chairs, a shade and perhaps some stationery. Most of these operators also sell prepaid phone cards and some offer an array of other accessories such as chips and skins. Some simply attach this service to some other business they already have, such as a convenience store or hair salon (Figure 4)

|

| Figure 4: Mobile phone service at a convenience store |

Currently these businesses do not require any license to operate and can set up shop wherever they wish. Although there are metropolitan regulations against street vendors, it seems none have encountered any problems from the Accra Metropolitan Assembly so far. It may be necessary though, to get permission from shop owners if setting up on the pavement in front of their shop. Some operators own the business themselves while others work as employees of some other person such as a relative or friend.

As regards social and economic impacts of this system, it seems intuitive that it not only provides expanded access to telephony, but also addresses telecommunications policy failures (in ensuring interconnectivity), and provides a source of income for several individuals. However, these possibilities remain to be assessed.

This is only one of innovations in telephone access and usage observed in the country. Other developments that would bear a closer look include:

1. Company-led initiatives providing mobile-to-mobile phone services – For example, Spacefon has recently outdoored two versions of a service it calls i-Tel “Pop.” The first is a manned service station where users can make wireless phone calls from payphones (Figure 5).

|

| Figure 5: Spacefon-Tel “Pop” station at the University of Ghana |

The second is a mobile service provided by bicycle riders (Figures 6 and 7). According to one such operator, there is the option to run the service as an employee of Spacefon (the option he chose) or as a personal enterprise.

|

| Figure 6: Spacefon mobile I-Tel “Pop” station |

|

| uFigure 7: Spacefon mobile i-Tel “Pop” station |

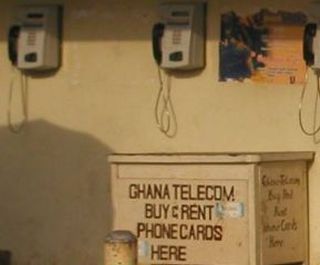

2. Renting of prepaid phone cards – Users can use the code for a prepaid card to make a call at a payphone and pay the vendor only for as many of the units as were used. The vendor then provides the code to another client, and so on until the units on the card are depleted. This was observed as a service provided by Ghana Telecom (Figures 8 and 9) but may conceivably be happening between individual subscribers as well.

|

Figure 8: Ghana Telecom phone card rental station

|

|

| Figure 9: Ghana Telecom phone card rental |

3. Sharing of mobile phone handsets – this is increasingly happening at the individual level and was observed in a form that eliminates accounting issues. In this case, a person can remove the chip from their cell phone (e.g., if the phone battery is running low or the handset is faulty), place it in a friend’s cell phone, make a call and then remove their chip. In this way, the cost of the call goes to the owner of the chip that was used, as if they made the call from their own handset (chips can cost around 200,000 cedis).

Most of these are fairly recent and on-going developments that provide an opportunity to observe the social shaping of technology in the context of developing countries. What is especially significant about these developments is that for the most part they are end-user driven. So far there appears to be no donor or government involvement in developing these systems, and the large-scale business community is largely responding to rather than driving the developments. As against exploring the potential of ICTs to contribute to social and economic development, this is an opportunity to examine actual uses and impacts arising out of micro level adaptations of available technologies. Possible issues or questions to be investigated include:

- How did these services and usage patterns emerge?

- How are they being deployed?

- What is their distribution, in particular between urban and rural locations?

- What types of people are offering and using these services?

- What impacts are they having on the lives and livelihoods of operators and end-users?

- What factors may affect the long-term sustainability of these systems?

- How are markets and individuals adapting wireless telephony systems to local conditions?

- What can we learn about the intersection of macro, meso and micro levels of ICT impacts in the context of developing countries?

References

Kelly, T., Minges, M., & Gray, V. (2002). World Development Report 2002: Reinventing Telecoms. Available at:

www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/publications/wtdr_02/material/WTDR02-Sum_E.pdf

.